This is the first of a series of articles devoted to ‘Mapping the Brain Circuits’.

In the series I hope to explain in simple terms how connections between the PFC, Basal Ganglia, Midbrain and Limbic System are involved in learning and habit formation and more importantly how we can influence their functions in a positive way.

Metaphorically when we talk about our ‘map(s) we are describing how we/our minds navigate, or operate, on a day-to-day basis. Some of our maps give us limited choices as to how we react in a given situation. Unhelpful or even destructive thinking and behavior may result.

Being able to evaluate, potentially regulate and determine the intensity of a particular response is especially important when we want to change a habit.

With a better understanding of how we create our maps, both at a neurobiological and a functional level, we should be able to make better choices from a wider range of options. In other words we should end up with a superior map.

The PFC is the centre for ‘Know-No’ control

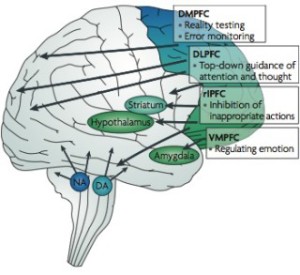

Under non-stress conditions the PFC circuits are responsible for orchestrating brain activity involved in thought, behaviour and emotion. When these circuits are operating effectively, sometimes called the ‘Delicious Cycle’, they utilize optimum levels of noradrenaline and dopamine. (see image below. DA: Dopamine; NA: Noradrenaline)

However as we shall see these ‘cool’ functions may be impaired by excessive “hot-system’ activity associated with higher levels of the stress hormones noradrenaline and cortisol. It is therefore not surprising that some of the solutions include strategies for reducing stress and strengthening the self-control ‘muscle’.

Making choices can be informed either by our perception of the value of that choice, in other words ‘Knowing’ the best or most rewarding option. Or it can be in response to self-control: the ability to say ‘No’ to an unhelpful or unwanted response.

The ‘Know-No’ functions in the PFC are where our most advanced thinking or ‘executive’ function is carried out. This is also where activity, or sometimes as far as habits are concerned, lack of it, makes a difference to how we function as individuals: how we interact socially, our level of insight, foresight and initiative.

How is the Pre-Frontal Cortex designed to carry out its functions?

The Pre-Frontal Cortex is part of the Neocortex characterized by up to 6 horizontal layers of pyramidal and other cells which interconnect with other parts of the brain. The layering helps to sort out a myriad of input connections from output connections.

For instance the PFC receives inputs from sensory areas providing information about environmental temperature, painful stimuli, and touch etc., as well as from motor and limbic areas.

There are also Association Areas within the PFC which ave single specialist functions such as the ability to recognize objects, colours and faces.

Damage to the frontal cortex can occur suddenly with conditions such as a stroke. Less permanent dysfunction can be caused by chronic sleep deprivation and/or stress.

Many of us can relate to the manifestations of chronic sleep disturbance where our emotions may be labile and/or on a ‘short fuse’ or even quite flat. We may have difficulty maintaining attention, feel lethargic, less interested in our surroundings or other people and loose our ability to be creative.

Specialist PFC areas and their connections are involved in habit learning and change.

Different areas within the PFC are responsible for different aspects of our executive function including self-control, being able to focus and make deliberate choices.

The ‘Deliberation Circuits’ include the PFC and its connections with the Striatum in the Basal Ganglia and the Midbrain. These circuits are where supervision and monitoring of new and existing learning, including of habits, takes place. It is also where we choose one option over another, an important aspect of being able to veto a habitual response.

The Inferior and Lateral part of the PFC, particularly in the left brain, is important in being able to resist immediate rewards, to say “No”. (see image: rIPFC: right inferolateral PFC)

Research has shown that when activity in this part of the PFC was disrupted by transcranial magnetic stimulation, participants chose the sooner-smaller immediate reward rather than the larger-later delayed reward.

Bernd Figner and his colleagues who carried out this research postulated that this response was more likely due to an induced impairment of self-control (the ability to say “no”), rather than the ability to weigh up the options.

The Dorsal and Lateral Prefrontal Cortex: (see image: DLPFC) are important for the regulation of attention, concentration and focus, task-related working memory and the logical aspects of problem solving.

Learning how to strengthen the ability to focus, that is selectively attend to one thing and avoid distractions, either sensory or emotional, is a function of connections between the PFC and Anterior Cingulate.

Daniel Goleman in his book Focus[1] says that when we learn to focus effectively we make better decisions, adhere to our guiding values and intuitions and navigate more wisely. In other words we create a superior map.

Orbital (Orbitofrontal) and Medial areas (see image: VMPFC) are important for the emotional aspects of planning and decision making and have extensive connections with the ‘hot’ Limbic system including the Amygdala, the Nucleus Accumbens in the Basal Ganglia and the Hypothalamus.

As we shall see later when we look at the control of our eating habits, functional MRI scanning has shown increased activity in the these areas, particularly those associated with reward and reinforcement, when subjects are exposed to palatable foods such as chocolate cake or pizza.

A summary of the how the PFC functions in relation to habitual learning and responses:

- This area is where we make choices either by evaluating which is the most appropriate or rewarding and/or by calling on our self-control.

- However the deliberation circuits are more complex, reflective, and slower than the bottom-up habit circuits based in the Basal Ganglia.

- When we are learning new habits, the PFC is where the ‘decision’ whether to hand over control to behavioural areas in the basal ganglia and/or decide whether further monitoring is required, is made, albeit sometimes we are not consciously aware of this.

- The PFC develops later than the Limbic system and its functions, including the self-control or “No” function, may be attenuated by stress.

- The PFC functions take relatively more effort and energy to operate than the emotionally driven ‘hot’ Limbic system.

- However we can learn to overpower automatic reactions, mute emotionally driven impulses, and can even suppress primitive reflexes[2].

Next up: The Basal Ganglia: The bottom-up ‘engines’ for habitual learning and responses

[1] Daniel Goleman. Focus: The hidden driver of excellence

[2] Daniel Goleman. Destructive Emotions: A Scientific Dialogue with the Dalai Lama